Aspartame is an artificial sweetener discovered in 1965 and approved for human consumption by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1974.

Concerns about the safety of aspartame, including a possible link with cancer, have long been raised. In fact, the FDA revoked its approval in 1980, before reinstating the ingredient as safe a year later. The sweetener is considered to be one of the most studied food additives in our food supply, prompting regulatory reviews by more than 100 government bodies.

In recent weeks, aspartame has again grabbed global mainstream headlines, culminating with the published findings of two World Health Organization studies into its safety.

The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) said aspartame should be added to the list of possibly carcinogenic substances.

However, IARC’s review and subsequent classification does not take into account the amount a person consumes and its classification places aspartame in the same category as aloe vera and caffeic acid (commonly found in tea or coffee).

A separate report by the Joint Food and Agriculture Organisation and WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) said it had not found convincing evidence of the link between aspartame and cancer.

The JECFA review said it would maintain its guidance that aspartame was safe to consume in moderation. It continued to recommend people keep consumption of aspartame below 40mg/kg a day, a level it first set in 1981.

For the average person, this would be equivalent to between nine to 14 cans of diet soda per day.

Earlier this year, the WHO published guidance stating replacing sugar with non-sugar sweeteners like aspartame in food and beverages does not help with weight control.

It added that non-sugar sweeteners were “not essential dietary factors and have no nutritional value”.

Dr Francesco Branca, director of the department of nutrition and food safety at the WHO said: “Science is continuously expanding to assess the possible initiating or facilitating factors of cancer, in the hope of reducing these numbers and the human toll. The assessments of aspartame have indicated that, while safety is not a major concern at the doses which are commonly used, potential effects have been described that need to be investigated by more and better studies.”

The food and drinks products containing aspartame

Since its approval by the FDA in 1974, the artificial sweetener has been sold as a sugar substitute since the 1980s, predominantly by the brands NutraSweet and Equal.

Aspartame is used in products ranging from ice cream and chewing gum to instant teas and coffees, as well as most commonly in ‘diet’ or zero-sugar soft drinks.

It should be noted the sweetener does not fare so well when heated to a high degree in cooking processes as it losses sweetness, thus making it less desirable for baked foods or goods that must endure prolonged high temperatures during production.

Both The Coca-Cola Co. and PepsiCo have been using aspartame in their beverages since 1983. Coca-Cola first used it as an additional artificial sweetener blended with saccharin.

The reaction to the WHO reports

In the main, the beverage and sweeteners industries welcomed the findings of the two WHO reports. However, there is some concern about mixed messaging. The IARC (in its first review of aspartame) classified the sweetener as “possibly carcinogenic to humans”, while JEFCA (on its third assessment) said there is “no sufficient reason to change” the previous guidance on consumption.

In response to the findings, the International Sweeteners Association sought to underline the assessment from JEFCA.

“Aspartame is one of the most thoroughly researched ingredients in the world. As part of its comprehensive assessment, reconfirming the safety of aspartame, JECFA examined IARC’s conclusions and found no concern for human health. Importantly, IARC is not a food safety body and its 2B classification does not consider intake levels nor actual risk, making an IARC review far less comprehensive than the thorough reviews conducted by food safety bodies like JECFA and potentially confusing for consumers,” the trade body said in a statement. “To put this in context, IARC’s 2B classification puts aspartame in the same category as kimchi and other pickled vegetables.”

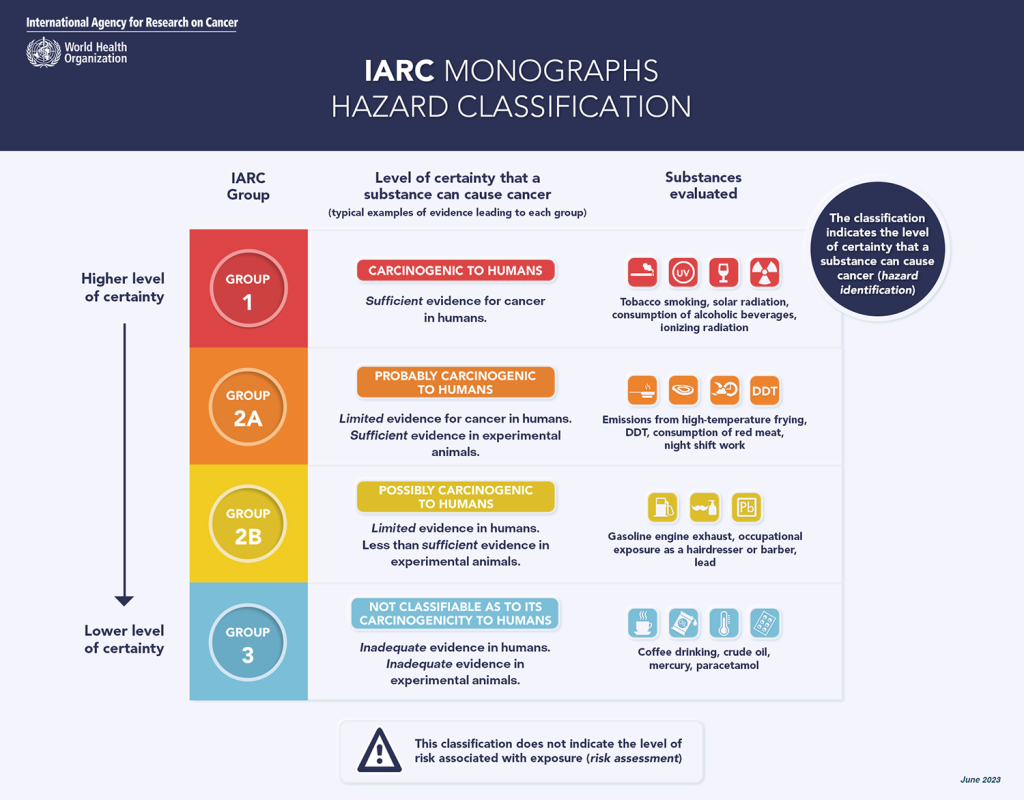

The IARC’s classification is based on its ‘Monographs Hazard Classification’ table. It contains four classifications: ‘carcinogenic to humans’; ‘probably carcinogenic to humans’; ‘possibly carcinogenic to humans’; and ‘not classifiable as to its carcinogenicity to humans’. The IARC already includes in the ‘2B’ classification radio frequencies, lead, marine diesel fuel and petrol engine exhausts.

The IARC’s conclusion drew criticism from the US FDA. “The FDA disagrees with IARC’s conclusion that these studies support classifying aspartame as a possible carcinogen to humans,” the US food regulator said.

“FDA scientists reviewed the scientific information included in IARC’s review in 2021 when it was first made available and identified significant shortcomings in the studies on which IARC relied. We note that JECFA did not raise safety concerns for aspartame under the current levels of use and did not change the acceptable daily intake.”

Amid a slew of headlines last week that contained phrases such as ‘cancer risk’ and ‘aspartame carcinogenic’, there are concerns consumers may shun food and drinks containing artificial sweeteners in favour of sugar.

Jamie Cartwright, a partner at London law firm Charles Russell Speechlys, says the WHO’s latest review could confuse consumers.

“Ensuring that consumers have the right information is paramount but a balance needs to be struck to avoid overwhelming or confusing them, and it is important to carefully consider where aspartame sits on this scale,” Cartwright explains. “The key lies in managing how any health implications are communicated in line with the risk associated with the product while being cautious not to dilute key messages that are necessary for consumer awareness.”

Popularity of aspartame could sour

Beverage manufacturers (or their representative bodies) using aspartame have not been eager to comment on the IARC’s classification of aspartame. Some have been quick to point to the FDA’s rebuke of WHO, while many referred questions to trade associations and the ISA.

No major beverage company has come out to say it will replace aspartame in its products. PepsiCo CFO Hugh Johnston told Reuters last week the group did not intend to change any of its recipes that included the ingredient.

Among aspartame’s benefits is that it accentuates certain flavours, particularly citrus fruit flavours like lime, lemon and orange.

Nevertheless, Steve Osborn, a director at UK-based Aurora Ceres, which offers food technology and innovation support for food and drinks manufacturers, suggests some companies may move away from using aspartame, although he underlines the ingredient has already been facing competition.

”The recent public discussion will not have helped and we may see a shift away from aspartame toward other sweeteners but this has been the case over the last ten years or so since the introduction of stevia-based sweetening solutions, and some of the sweet proteins and taste modulation technologies that helped to balance the overall mouthfeel as well as sweetness,” Osborn says.

“Aspartame will take another hit from this but it is under greater threat from innovations in sugar reduction technologies such as the availability of lower-calorie sugar replacers such as tagatose and allulose, which have been growing in commercial availability and over-coming novel foods hurdles in Europe.”

In the wake of the WHO findings, manufacturers are unlikely to move away from aspartame for reasons of product safety. However, the potential for consumer confusion and the ongoing development of alternative ingredients could give product developers food for thought.